An Interview with Cody Bratt

CONTOS —

Selected for the Director’s Choice Award, The Other Stories project questions family inheritance in various ways. You explore what has been passed down to you through the generations– you credit your grandfather for introducing photography to you and even mention the 1952 Hasselblad he gave you. You account for your great-grandfather’s archive of 2,000 negatives and describe both these men as significant figures in documenting and perpetuating labor movements. Through the lens and archives, these figures are depicted as champions. However, this project is centered on the untold stories of substance abuse, domestic violence, and neglect. Stories such as these exist in all of our families. At least I assume they do, as they certainly exist in my lineage. Your project statement frames these stories as “inherited darkness,” and you question what your personal responsibility is in relation to ancestral trauma. While you worked on this project did you discover an answer to your question? Did you determine what your responsibility is for this inherited darkness?

BRATT —

I’m still knee-deep in making The Other Stories. I’m about forty to fifty pieces in at this point and between the two-thousand photographs in the archive, the printed archive material, and the digital and mixed media processes I’m working with, there are probably countless ways to chart a path through the entire body of work. It can be an overwhelming journey at times, like feeling lost in an ocean. I’ve still not found all the answers to these questions and I’m guessing some will remain elusive.

That being said, I have decided — for better or for worse — that sunlight is the best disinfectant. If you zoom out to the macro-cultural context here in the United States, we tend to repress and deny the negative, violent and shameful moments and replace them as “truth” with magnified versions of the positive. We have trouble accepting two simultaneous, but conflicting truths: that we can be capable of tremendous good and almost bottomless darkness. On the whole, I guess that most families developing in that context tend to follow suit. And we see how that has played out on the national scale. All of that history catches up with you; there is no free lunch. The path I’m taking in this body of work is to attempt to acknowledge those hidden histories and integrate them into a wider whole to try to heal. But, there’s obviously a fine line here between what’s “too personal” and “fair game” — I have to reckon with this individually on every piece I create and I’m not sure I’m a fair judge of whether I walked that line sufficiently.

CONTOS —

What drove you to take this on as a project?

BRATT —

There are both emotional and practical answers to this question. An emotional answer is what we were just discussing. On the pragmatic side, I’ve been fascinated by the physicality of both mixed media projects and archives for some time. Here’s an anecdote: almost twenty years ago, I was the Editor-in-Chief of our high school yearbook and my volume was the 87th volume. Before breaking ground on it, I painstaking went through the other 86 volumes back to 1914 to create a mood board of sorts to bring that history forward in both design and execution. The physicality of those archives really captivated me. So, in the context of my art practice, I was looking for ways to push my own vocabulary and bring in my propensity to be an archeologist. I started The Other Stories about a year before the pandemic began, but as the pandemic has worn on, obviously this particular project has been well suited compared to my normal way of making images.

CONTOS —

I can relate to the question of responsibility, and for many of us we must ask what we will carry forward from our heritage and what must be left behind, but few of us would turn to art for resolution. Why was art the method of investigation? Since it was art that you relied on, did you always intend to publicize this intimate series about the hushed stories of your ancestors?

BRATT —

I think I ultimately chose art as the investigatory path because I can’t help myself.

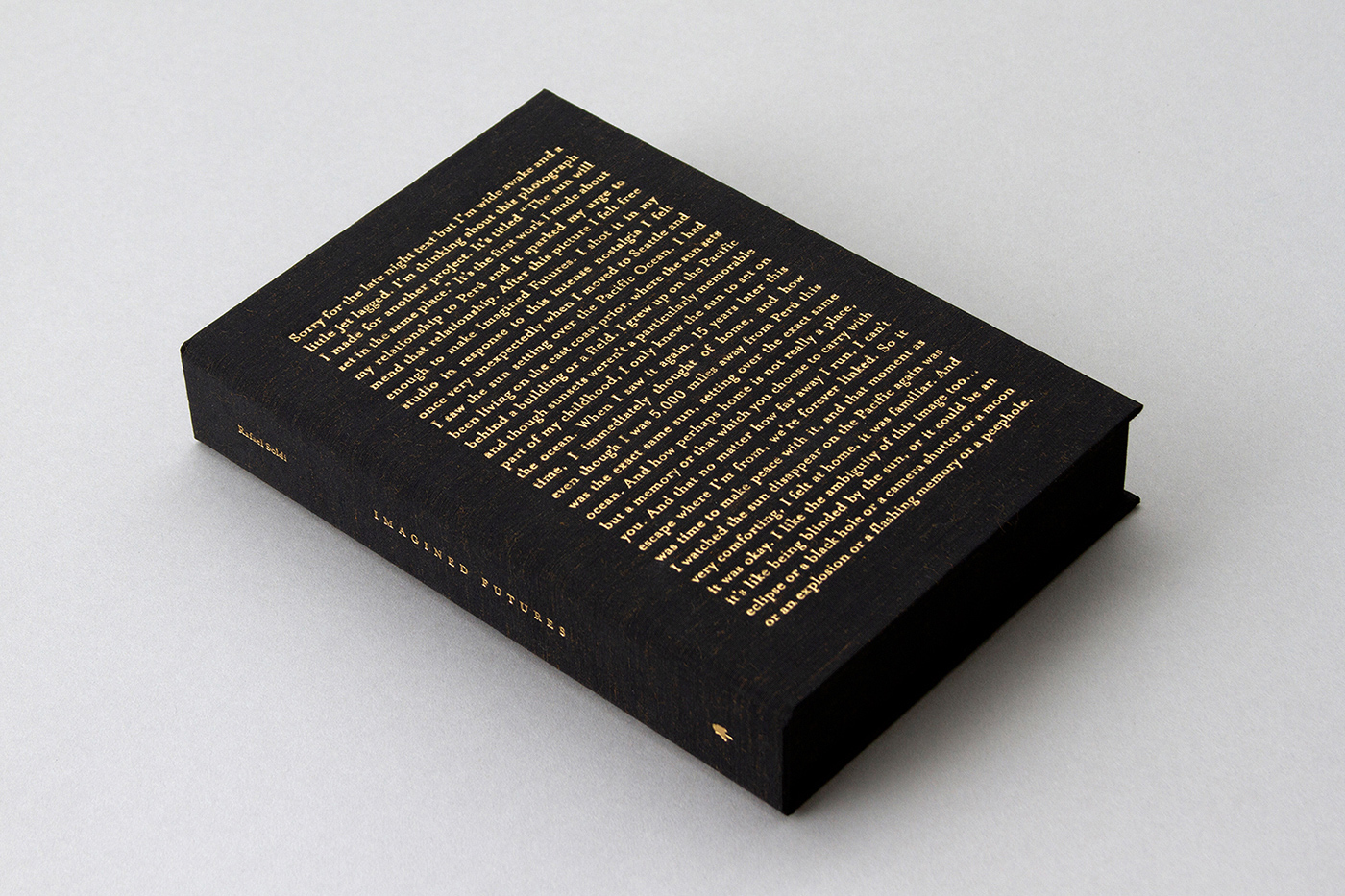

I’ve always investigated things creatively and — in this instance — the whole of what I had in front of me to work through was visual. And, to a degree, the whole notion of inheritance even came about, to begin with as a result of me publishing a book of my last body of work. So, investigating through art was the only choice.

I’m a bookmaker at heart and, given the fact that the last time my great-grandfather worked with these pictures was on an abandoned book project, it seems obvious to me to realize it in book form at some point. But, it took me over a year of working on the series to begin to share it publicly, largely for some of the ethical reasons above. The CENTER Award is the first time I’ve shared the work widely online and this interview is the first time I’ve talked at length about it. Bringing other folks in on it is difficult, but natural.

CONTOS —

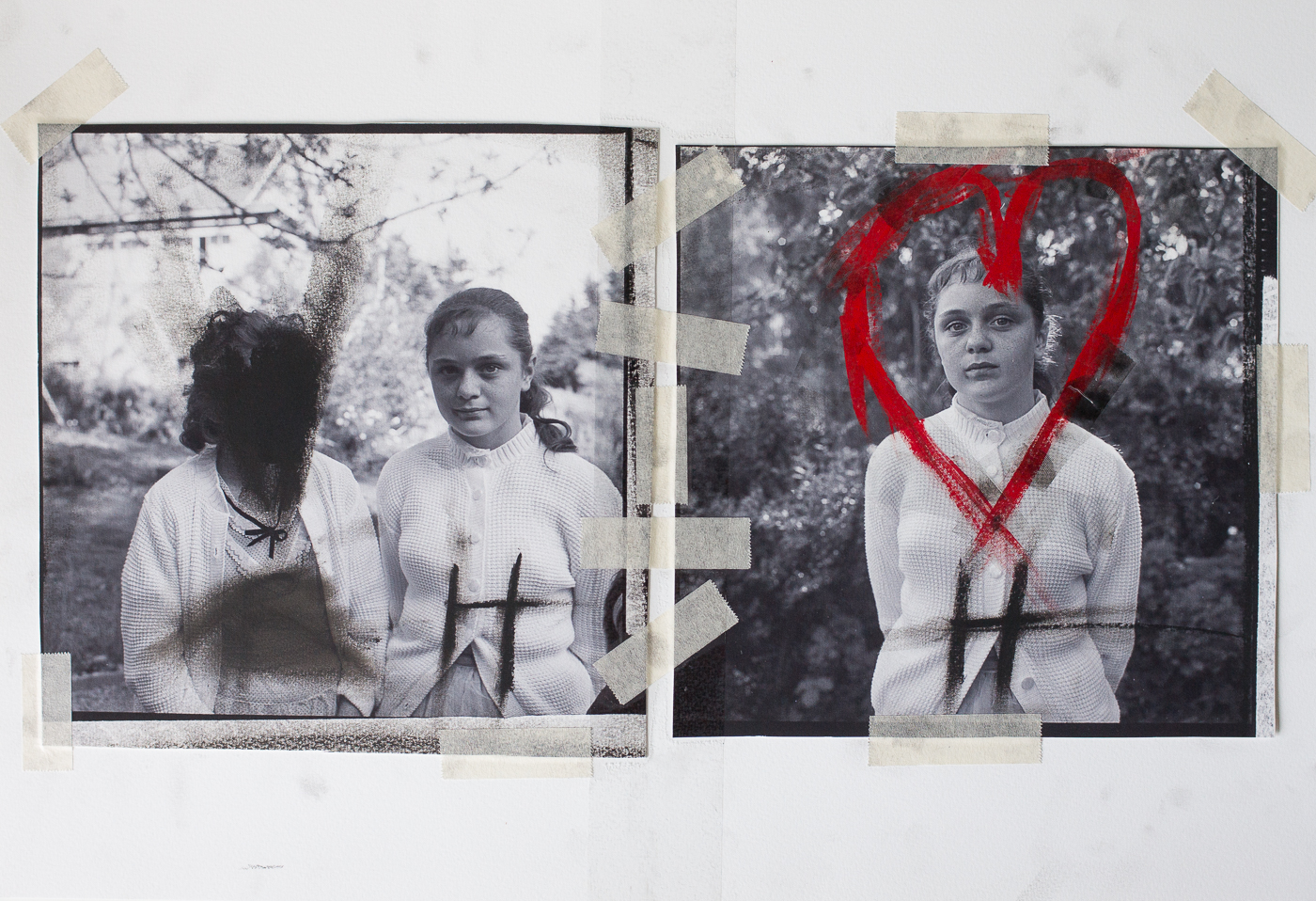

This is a mixed-media series, which from what I know if your work is a bit of a departure from previous works. The aesthetics are very powerful in this format, it is truly compelling and rich work. The many layers of media combine well with the ambiguity of which parts of the work were repurposed family photos and which parts you added later. The final outcomes leave the viewer in a little bit of a loss in the chronology, the origin, and the author. I think memory, and in particular, trauma works this way too, as it makes us wonder what bits of ourselves, good or bad, were inherited and which are of our own making. Can you talk about the process of creating this series? What constituted a departure from former approaches to your subjects? How did you arrive at your choice of using mixed-media?

BRATT —

My typical approach to making photographs up until this point involved creating narratives in a “lightly controlled Mets luck” sort of way, leading to my debut book, Love We Leave Behind. For example, I’d exert control through model casting or the general direction I’d head on the road, but I’d leave to chance other details like wardrobe, makeup, posing, time of day, the specific route taken. All the photographs in that body of work are made with a digital Leica, which — as a rangefinder — sort of embodies that control meets luck persona. I’m most influenced visually by well-crafted cinema, so those photographs really wear their inspirations on their sleeves in terms of their degree of glossiness.

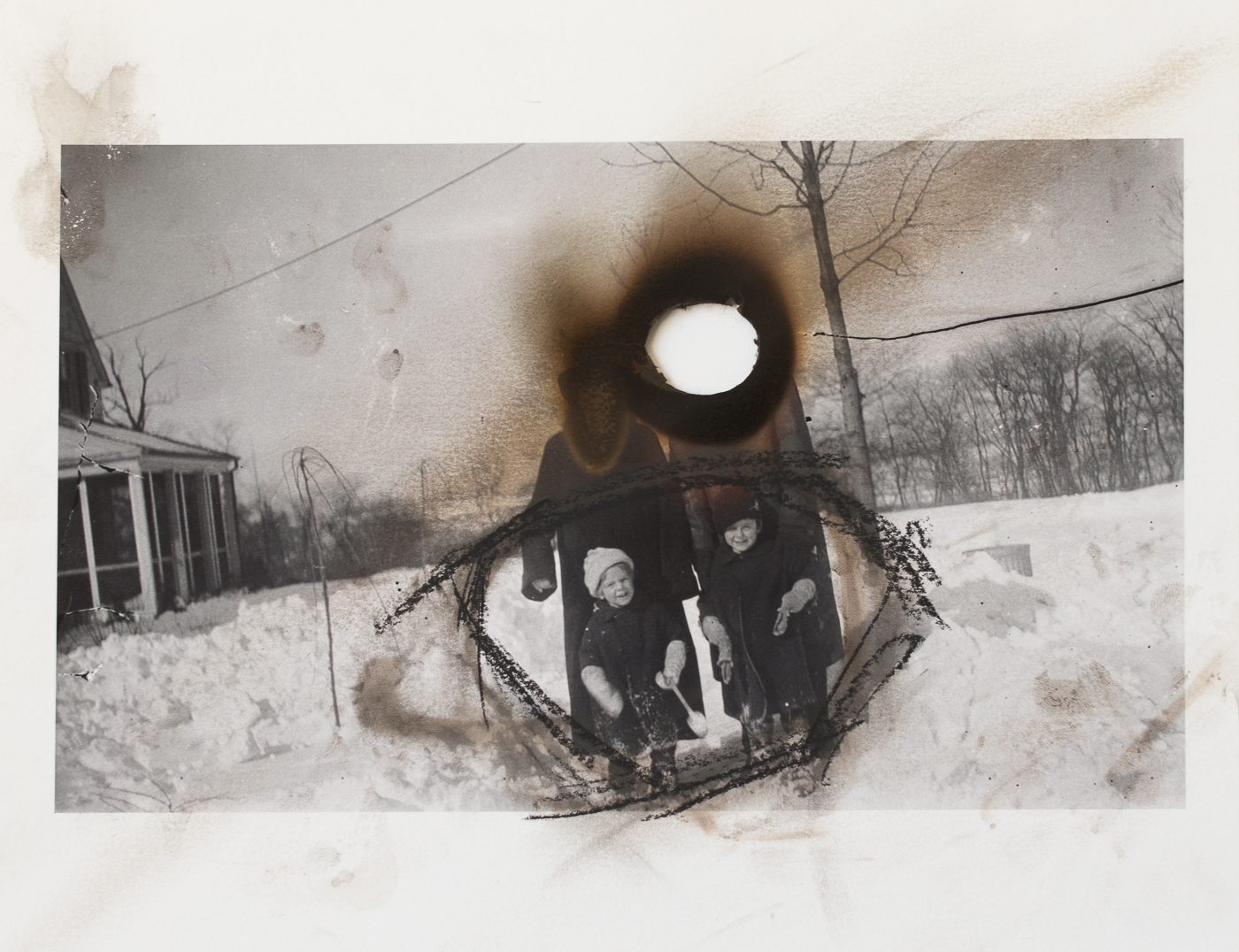

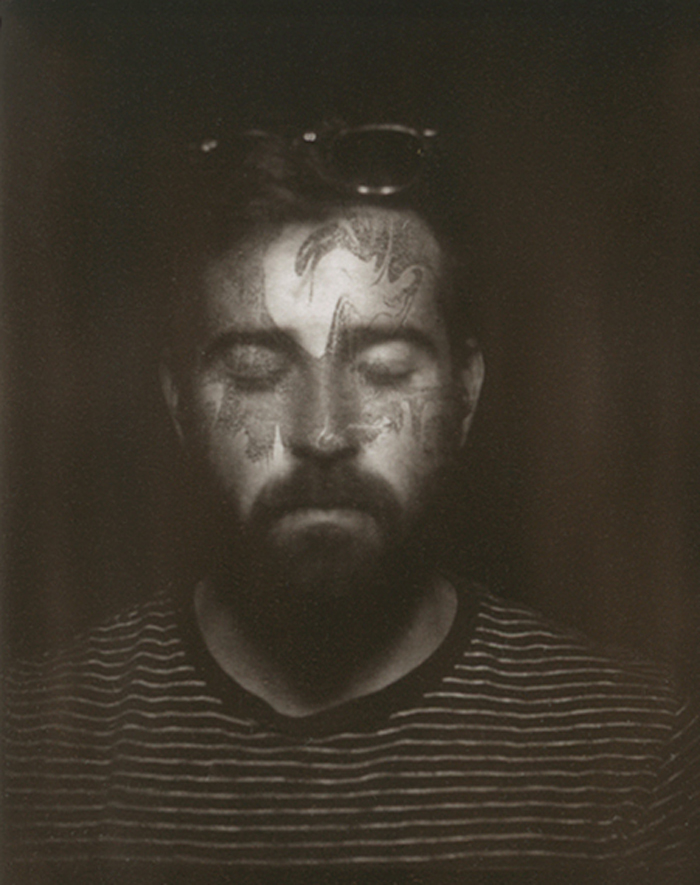

But, there is a big part of me drawn to the dreaminess afforded by things like instant film, vintage gear, historical processes, and mixed media. So, I’d been looking to start to expand my practice’s visual vocabulary. I had originally conceived of The Other Stories as two strands of images in conversation: one curated set of my great-grandfather’s photographs printed normally and a corresponding set of photographs made from scratch by me in my typical style in response. As I got into making the photographs, I found the contrasts between the two approaches didn’t integrate well, so I decided to lean into the archive photographs themselves and the historical processes they were created from. This forced me to exert my line of inquiry in another way, through mixed media and my graphic design instincts. That breakthrough has opened a door of possibilities across my practice moving forward.

Even though I’m still working on this body of work, my mind can’t help but occasionally wander to “what’s next” and I’m excited by the possibility of synthesizing the disparate approaches of Love We Leave Behind and The Other Stories into a singular approach which is more than the sum of the component parts.

CONTOS —

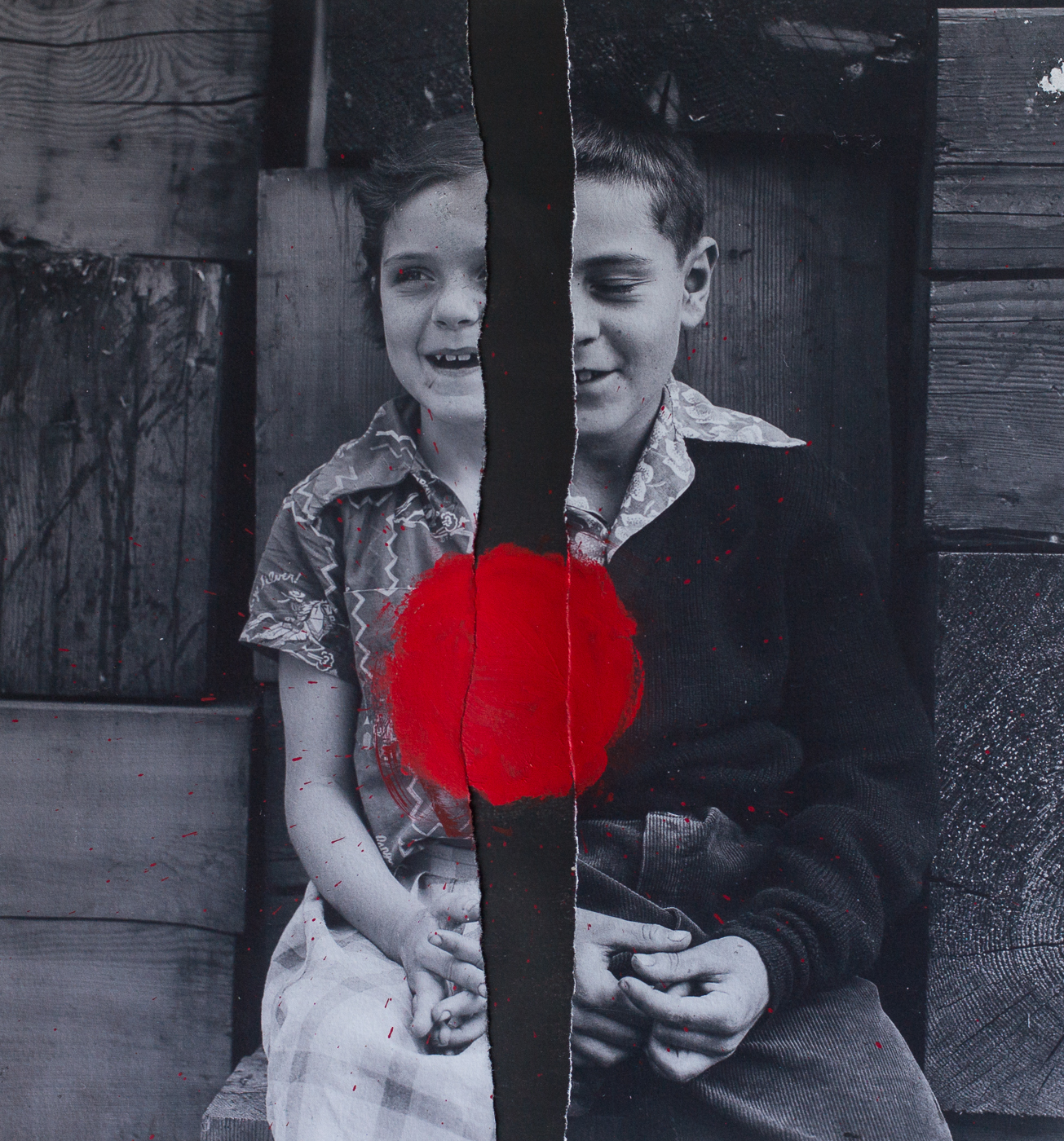

There are some recurring motifs as well, red circles, scratchy handwriting from what appears to be grease pencils, burns, tears, and red. I have only seen these works as digital images which makes me wonder how much I am missing from seeing them as objects in-person. How much is missing by viewing these on a screen, or what is lost when these photo-based objects are viewed as a digital image? How does your process reflect the content, and in what context to envision them being viewed at their best?

BRATT —

The issues you ask about were definitely things I struggled with in the beginning. The thought of working with entirely unique pieces was (and is still at times) terrifying, so after I shifted away from the approach I talk about above, I started making photographs of the archive photographs. Overall, these felt too flat and the overall physicality of the constructs I was shooting attracted me more, so I decided to fully commit down the unique piece path. I don’t anticipate exhibiting or printing anything other than the unique originals. I’ve found the physicality of the originals to be reasonably preserved on the screen, which is funny considering that I don’t like the prints of them.

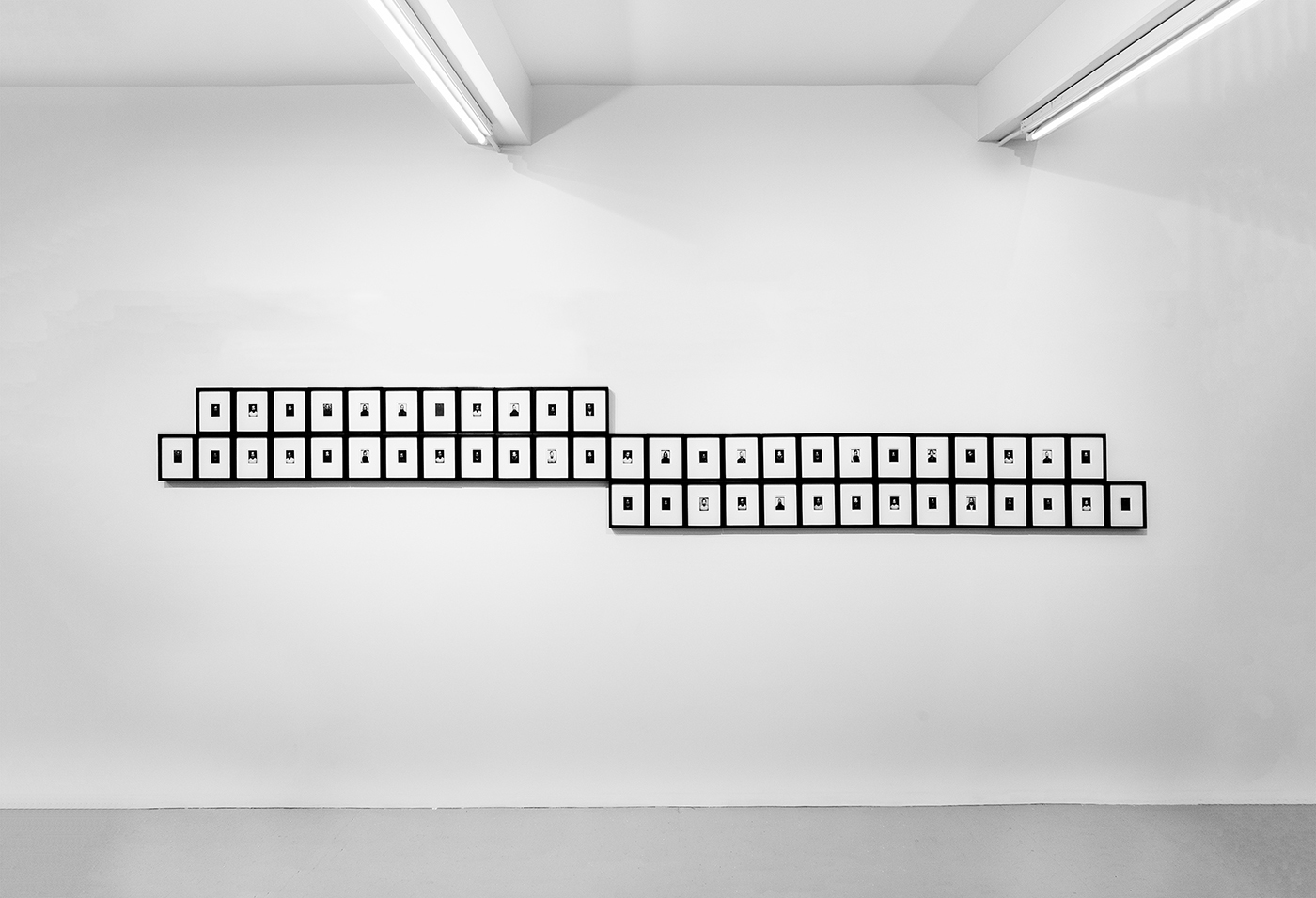

Even though I’m a bookmaker first, I’ve found that I’m most excited at the moment about the prospect of realizing The Other Stories on the gallery wall. That was surprising to me. The mechanics of the framing and displaying of the work on the wall coupled with the physicality of the original pieces themselves opens up a unique path for the series. This is especially true once you start to put twenty to thirty of the pieces onto the wall.

Stepping back, I think what this speaks to is that I don’t believe these mediums — the show, the book, the screen — to be “better” or “worse” than each other. Each one offers a unique model for the work to speak. The trick is finding the right way to adapt the work for each medium.

CONTOS —

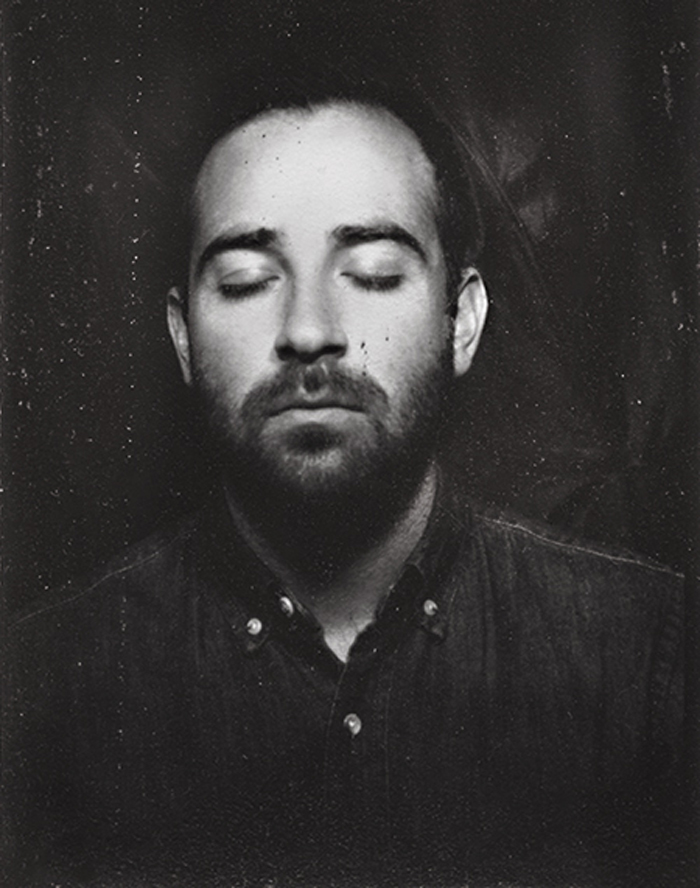

The content of the photographs in the work read like gentle memories: A man, presumably a father figure and little girls playing in the water, a family posing in the snow, and portraits like any other that are easy to imagine on a mantle in any house in the world. The photos alone read as something so familiar it is almost mundane. Yet, the photos are torn, the subject’s eyes are scratched out, some are encircled furiously, others taped together across brazen tears and red dots punctuate them with immediacy. The story behind the images and the markings made upon them are deep with emotion and meaning, yet the story itself is still untold. You talk about how you did not bear witness to the stories you are investigating in the project statement, and yet they have impacted you. They are not your stories exactly, and you can’t recall the events but clearly, something remains in the depths of your memory. As a viewer I can’t say that I am all that invested in the story itself, I am of course curious what the narrative might be. However, I do not feel like something is missing, instead, I find it easy to insert my own narrative, as if you created a space for others to enter. As you put this work together did you consider the viewer’s experience? Is it intentional to leave space for others to insert themselves, or is this perhaps my own ego kicking in? What do you intend for the viewer, if anything?

BRATT —

I very much consider the viewer’s experience in-so-far as I want them to have an experience considering the work — love it or hate it. It is definitely not your own ego kicking in. My intent is to leave enough space for others to enter, otherwise, I think the work would become overly specific and viewers would just bounce off. There is an added benefit here, which is that the act of conceiving of and leaving this space assists in avoiding the exploitative and ensures that the specific individuals pictured continue to have enough agency.

CONTOS —

What has the response been from others? Did your family engage with the work at all, were they part of the process? How did your family respond?

BRATT —

I’m particularly proud that a gallerist recently described the work as “relentless” as that’s the spirit under which I’m operating. Creating these works using base photographs that were not captured by my hand was very foreign to me and I’ve been very surprised at the depth of the supportiveness I’ve received in the approach. It’s really helped assuage any fears I’ve had on that front.

How my family has engaged with and received the work is a lot more complex. My parents kept me at arm’s length — correctly, in my estimation — from the side of the family I’m now exploring. The distance that opened up, along with both my mother and father’s transparency about the family, is a prerequisite to making the work. Similarly, my own interactions and observations of the family (both indirect relationships and through the photographs) add a separate inflection point. But, no one in my family has influenced with intent specific decisions about how I make the work. So, in those ways, the family was simultaneously both a deep part of and not at all part of the process.

My mother and father have been supportive. That my father is supportive is particularly meaningful since he is actually in some of the pieces as a child or young man. I’m not sure how much my extended family follows my practice, so I’ve not engaged with anyone else in the family about it. My expectation is that there will be deeply conflicted feelings and opinions depending on who you ask and my guess is that there may be some degree of validity to those feelings and opinions depending. My hope is that they’ll keep as open a mind about the work as I do about their feelings about me making it.

CONTOS —

This interview series is part of our Photography 2020 Compendium initiative wherein we are investigating the past, present, and future of photography. You are clearly part of a long line of photographers, and I wonder how you view the trajectory of photography? What has photography meant for the different generations of your family? How does it serve as a tool for the political arena? What have you witnessed as major shifts in the field, and what does it mean to be a photography today? Where is the field heeded, or where might you hope it goes?

BRATT —

Outside my fine-art practice, I’ve been employed in film labs and, currently, as a Product Manager for the Google Photos Print Store. I’ve watched my dad for my entire life help bring to life journalism, advertising campaigns, brands, and more through photo-engraving. My great-grandfather was telling stories both personal and political. Photography, at its root, is a tool by which we tell our own stories and myths, whether you’re referring to photography as a fine art field, or the vernacular use of the medium in albums and home, or its technical utilization in offset printing. We’re already seeing more people than ever be able to tell their stories and truths in situations where they might not have been able to in the past.

With this in mind, I anticipate photography will continue to find new methods and means by which it helps us make myth — just as it’s always done since its inception. Photography is often pegged by those inside and outside the field as somehow more utilitarian or real than fine art like painting. What those takes on photography miss is how highly adaptable photography has always been. It’s adaptable to the point that it can easily be grafted onto and evolve into many other mediums. I feel photography can become painting in a way that painting cannot become photography. This is incredibly freeing once you realize it and I think more artists, gallerists, and curators will discover this over time.

That’s not to say where the field is headed is all roses. The same adaptability that makes photography so strong as a starting vantage point in storytelling is the same adaptability that helps some of those in the political arena find new paths for increased disinformation and more effective propaganda. Tomorrow’s war is nowhere and it’s an information war. If photography was a supporting cast member of yesterday’s war, then it’s now become as central to waging war as the sword, the rifle, the machine gun, or the bomb.

Ultimately, I think this puts increased urgency on what we do as artists to tell our local and personal truths the best we can. What gives me comfort is that I know we’ll continue to rise to meet the occasion, even if we stumble a few times first.