9.25.20

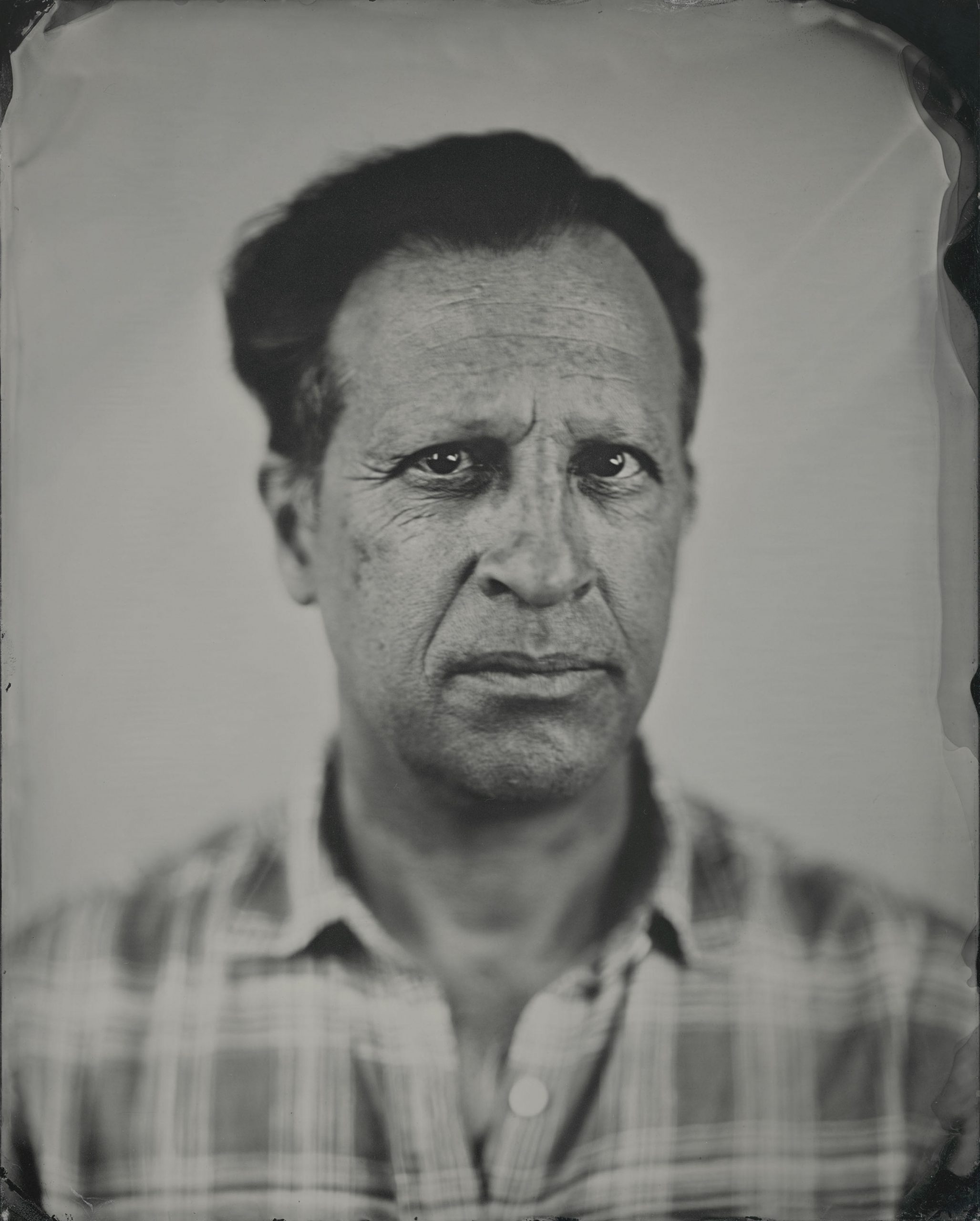

An Interview with Virgil DiBiase

By Matthew Contos, Curator of Public Engagement, CENTER

CONTOS —

Thank you Virgil for being in conversation with me about your project, My husband won't tell me his first name, which was selected for the Editor’s Choice Award. In researching your project I enjoyed discovering an overwhelming amount of content on your career as a Neurologist. You have also been widely praised for your photography skill set as well, and it seems the intersection of these two worlds you traverse makes for very powerful work. As someone with a neurological condition (Temporal Lobe epilepsy), I have found art to aid greatly in understanding my condition and in expressing to loved ones what it is I live with. I have found refuge in art practices and often use both written and visual arts as a tool for navigating the condition. The fragility of the brain, at least for me, has also allowed for discoveries of the brain’s resilience.

Given that your project is created with and about your patients, I am curious if your photography practice is useful within your medical practice? Have you found images, art, and art-making as useful tools for aiding in living with ongoing neurological conditions? Have your patient’s families become aware of your photography, if so what is their response to the work? It is very easy to see how the medical practice has informed the photography practice, but can you talk a little about how photography has informed the medical practice?

DIBIASE —

Photography allows me to socialize with my patients. Safe, social interactions, often lacking for them, cause our brain to release dopamine and serotonin creating positive, healthy emotions. Clinic visits can feel stressful but engaging with them in their homes, having coffee, and socializing is not. Consequently, when my patients come back to my clinic they recall me not as their neurologist but as the photographer-friend who spent time in their home. The concept of “home” is a more durable and permanent memory than an anxiety-laden clinic visit.

Art is an expression of our emotional well-being whether one has dementia or not. However, through social engagement and the discipline of art, photography, dancing, and music there is an opportunity to impact our emotional life via brain chemistry.

An example of this occurs in my community at a dementia daycare facility, where I am a board member. The focus at this facility is engaging the participants in art, music, dancing, cooking amongst other activities.

I don’t know if their families are aware of my photography, but they rely on me as a neurologist.

CONTOS —

In exploring your work I kept finding myself drawn into the titles of the photos as much as the images themselves. That might bother some photographers that I find the text as intriguing as the images, but the poetry is undeniably compelling: I understand you more than my left side, My Brain is fogged. It’s dirt, and even the project name itself, My husband won't tell me his first name, these titles offer insights to the work, but just as powerfully they offer insights into the conditions and experiences of dementia. How do you select the titles for the images, and what are the origins of these poetic lines? How do you view the relationship between text and image in your work? Is the use of text as significant to the use of images for you?

DIBIASE —

Over the years, I’ve accumulated quotes from my dementia patients. This is the origin of the captions. Like most photographers, I don’t care for captions. However, I try to find a way to interweave quotes with photographs and so this is my use of captions in this context.

I feel quotes are equally important to this project because that is the fundamental basis that drives this project. However, I think quotes can be overused, diluting the project.

Initially, I made portraits and then had the opportunity to collaborate with Larry Fink for several years. About a year ago he said, “you need to make perception photographs.” Perception? I thought what’s that? He said you’ll figure it out. In the midst of the pandemic, I’ve been making perception photos. Being temporarily relieved of my professional work due to the pandemic I retreated to the small farm my wife and I have, spending my time there. Retreating there I had a new focus, allowing me to put a magnifying glass on my subject and clicking the shutter at the very threshold before it burns. I notice now what is actually there more than before. The sun rising, sending rays through the woods, bats, swallows, weeds, shadows, and so on.

I usually have a quote in mind, go out into the woods, and make a photo. Once in a while, but not very often, they are a good match for the quote. Occasionally I dig into my archive. Most of the time I remember a quote and go out to make a photograph.

CONTOS —

My grandfather died while suffering from dementia. He was a quiet man as long as I knew him and much of his life was a secret to me. Towards the end, he often confused me for old friends of his past, and he spoke to me as if I were one of them. I learned more about his past in those final confusing and heartbreaking moments than I have ever had before dementia kicked in. There was something akin to a portal that opened into his past, and yet he still seemed so distant I could not share the joy of learning of his youth with him directly. Memory is a slippery thing, and photography for many is one of the primary ways of grasping and validating a memory. However, even an image can be untrue. It seems like memory and images are two things we rely on to understand our histories and in turn ourselves.

How do you perceive the relationship between images and memory? How has your work as a neurologist informed your interpretation of memory? How has photography informed your interpretation memory?

DIBIASE —

Photographs and memories, that’s a good question. Whether on a screen or in print photographs are visual objects. The print form uses multiple senses: visual, tactile, spatial, smell, and finger movement. A photo on a screen uses mostly visual input. That’s why I make handcrafted Pt/Pl prints. They are the most archival prints lasting maybe thousands of years. Memories are transient but Pt/Pl prints are permanent. Vision and memory are pretty well understood through neuroanatomy and neurochemistry. The eyes are the camera (or the video camera) of the outside world but the brain processes it into meaningful information, the internal world. Vision is the most prominent sense that we have, and memories are stored in the hippocampus, the memory center, along with other areas of the brain. And it’s no wonder that a photograph from the past triggers past memories. People with Alzheimer’s dementia, which is a neurodegenerative disorder that causes gradually declining language and comprehension of language, predominantly depends on vision and auditory sensation amongst others. It’s not that simple but vision and auditory sensations remain somewhat less compromised early in the disease process.

Anne Basting quote: “A memory is not an object preserved in the museum of our minds. It is a living, changeable thing that is shaped by who we are when we encode it and by who we are when we retrieve it.”

CONTOS —

In your project statement, you advocate for spreading awareness about dementia. You speak of the need for more financial support as the rates of those with dementia will increase exponentially until a cure is developed. Since the project's inception have you witnessed any improvements to the methodologies of treating dementia? Has your work been utilized in ways that have helped advocate for more support in treating dementia? How can we, the readers and admirers of your work support your efforts for advocacy?

DIBIASE —

For over a hundred years there has been no improvement in the treatment of dementia. While much has been learned about pathophysiology, there is no cure or effective treatment. To my knowledge, there has been no evolution in the care of dementia patients. They are usually socially isolated and often warehoused in long term facilities. Their only activities are to play Bingo and use coloring books. Obviously, this is inadequate as we know that integrating the arts along with music and dance allows for an authentic mental and emotional engagement. They have unlimited creative potential. We can do more.

Viewers can contribute a donation or volunteer to their local nonprofit day programs for dementia patients. Nearly 1 in 3 of us will develop dementia if we live to 80 years of age and nearly one in 2 of us will take care of someone with dementia. We will be them.

My work has not been used to advocate for dementia patients at this time. But I’m working on a book project.

CONTOS —

This interview series is part of our larger analysis of how artists in the 21st century are advancing lens-based media, and how lens-based media has become ubiquitous.

Can you speak to your trajectory with the medium? How have you seen the medium evolve in the past 20 years, or throughout your career? What speculations, hopes, or concerns do you have for the use of lens-based media in the future?

DIBIASE—

I can’t recall when photography wasn’t part of my life. It became branded on my brain the moment I stepped into a dark room with my father and saw an image appearing before my eyes, on a piece of paper in a tray with water and with a red light on. I believe it was my first language in some way because my father was a photographer long before I was born making beautiful 8 x 10 silver gelatin prints of his family. I thought every kid had a darkroom in their basement. Photography has evolved in the last 20 yrs., digital photography, Facebook, Instagram. An explosion of photographs. But they’re not photographs they are JPEG‘s and viewed on a monitor, not physical photographs. I prefer the handcrafted print which is a solid artifact. I combine digital photography with a handcrafted print as I use digital negatives for Pt/Pl contact printing. I feel photography is taken for granted these days with the use of the iPhone and lacking consideration for the craft. However, I think the abundance of people participating in the visual language of photography is a good thing. I believe ( and hope) there is a resurgence of alternative photography practices. I don’t know about the future of photography, but it is here to stay for now.

Biography

Virgil DiBiase (b.1963) lives in rural Indiana with his wife and a bunch of equines. He is a full-time clinical neurologist, photographer, part-time farmhand. His parents were Italian immigrants who moved to rural Salem Ohio in the 1950s. His father was a photographer and taught him how to develop B&W film and make gelatin silver prints in the basement darkroom. Back then everything was in B&W: TV, magazines, newspapers, and photography. His father made beautiful family photos with his Leica and made big 8×10 prints. Black and white photography was his first language and so he continues to work in B&W.

vdibiase.zenfolio.com →