9.10.20

An Interview with Rafael Soldi

By Matthew Contos, Curator of Public Engagement, CENTER

CONTOS —

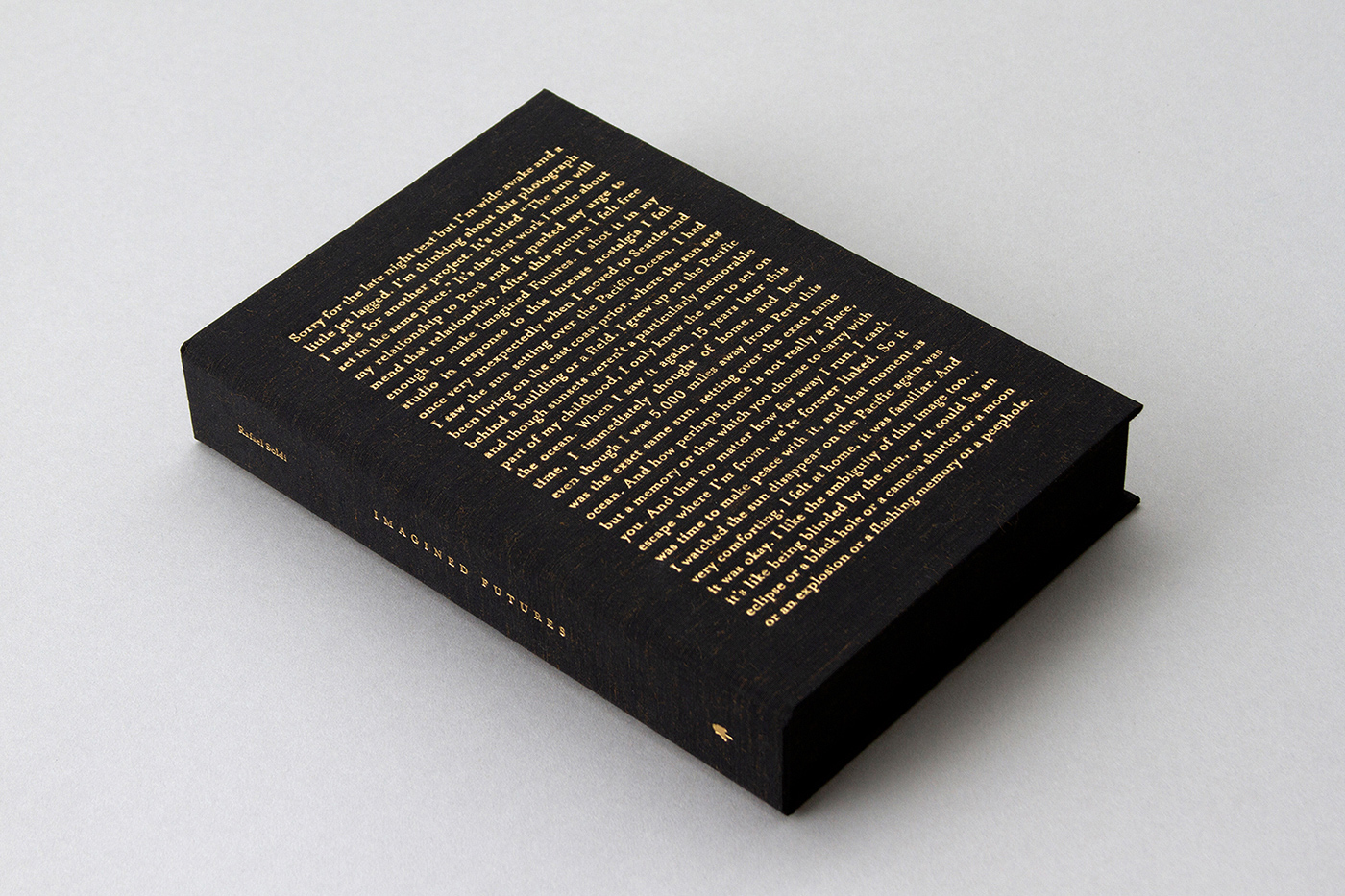

Your project Imagined Futures was selected for the Curator’s Choice Award, the project explores concerns that you describe as universal to queer immigrants. In your practice, you have integrated your own experience as a queer immigrant originating from Peru. The work feels like a portal into personal complexities of living in an age that is widely situated within identity politics, for better or worse, often defining how each of us relates to one another.

How do you navigate the relationship between the personal and the political in your practice – are they inherently intertwined in your work or are there elements that distinguish them as separate constructs?

SOLDI —

I don't think of it in such binary terms; I mostly focus on my personal experience with the full awareness of the political implications of a queer Latinx body taking space in institutional spaces and conversations. Imagined Futures addresses concerns universal to most immigrants, regardless of their sexuality. My experience, however, is colored by my queerness. To be an immigrant is inherently political—to leave your home in order to embrace a different one is a very difficult choice. All of my work weaponizes my personal experiences to bring light to larger issues of our time. I believe that the more personal something is, the more universal it becomes.

In Imagined Futures, I access this idea of the futures we didn't get to live in our home countries, and the persistent thoughts of what our lives might have looked like had we never left. Many people think of immigrants in the present tense, where we are presumably better off than where we were before. But most immigrants don't want to leave their homes, we have to. So for me, the political or radical act here is in affirming that immigrants have complex identities and relationships to their homes before they even get here. Immigration does not have to be an act of erasure—through this work I propose a new way to honor and release a past that may haunt you.

To be an immigrant is inherently political—to leave your home in order to embrace a different one is a very difficult choice.

CONTOS —

Beyond the dichotomy of personal and political, you also reference the individual and universal, framed as a private ritual that is then shared publicly. The dichotomy seems like an important element in Imagined Futures, which presents a few seemingly opposing concepts that first appear to be polar ends of a spectrum. Yet somehow, the work transcends the polarity in a way that illuminates the vast space between two concepts. For example, the individual loss you mourn in the portrait becomes representative of the universal mourning of all those who have left life at the expense of an imagined future. Similarly, you perform a private ritual to produce the images, and still, the public component of sharing that intimate space blurs the lines between what is public and what is private.

I come across a lot of work that rests on one end of the spectrum or the other, what influences your choices to work on the entire spectrum between the individual and universal, or between the private and public? Is dichotomy, or the space between two opposing concepts familiar terrain in your practice?

SOLDI —

This has been a long-time struggle in my practice that I have learned to balance. I've always made autobiographical work but am fearful of the trappings of narcissism. So I work really hard to make sure my work tells my singular experience but always reflecting on a larger universal concept. The specificity of my stories has proven fruitful—humans are curious by nature and pine for an intimate look into someone else's life. I try to capitalize on that curiosity to then engage the viewer in a larger conversation about topics I'm interested in: immigration, queerness, masculinity, colonial intervention. This project, more so than any others, really played with the concept of private and public on a lot of different levels, both conceptually and formally. In my work, I think in layers, with each layer being a point of access. I try to remain aware that some people may access the work through its formal qualities, while others may identify with the themes in it. As each layer is peeled, there are always ways to go deeper. I find it respectful to, at the very least, honor the person who does not like my work by investing in thoughtful, considered, professional presentation. Very often I see work I do not like, but I can appreciate the effort an artist has put into presenting their work professionally and thoughtfully. As a viewer, I feel respected and that's one small way to positively access the work for me.

This project, more so than any others, really played with the concept of private and public on a lot of different levels, both conceptually and formally.

CONTOS —

Imagined Futures emphasizes the significance of mourning, as a ritual and what seems to be a healing process of letting go, or perhaps finding closure around something that was never realized yet imagined so vividly its realness is undoubtedly valid. You describe the choice of using a photo booth as akin to a confessional, an apparatus of the Catholic sacrament of confession. The ritual quality to your process for this project seems like a very significant element in the work.

How does ritual inform your practice? Most rituals have distinct beginnings and ends, confession for example, typically begins with atonement and results in one reconciling their sins with God and obtaining forgiveness and mercy. Where does the ritual for Imagined Futures begin and end? Is it a personal ritual the audience bears witness to, or are the viewers somehow intertwined in the process?

SOLDI —

Though my work has always been introspective, this is the first time I actually employed a ritual. The connection to the Catholic confessional presented itself in the process. I made the first work for this series on the eve of Donald Trump's election in 2016.

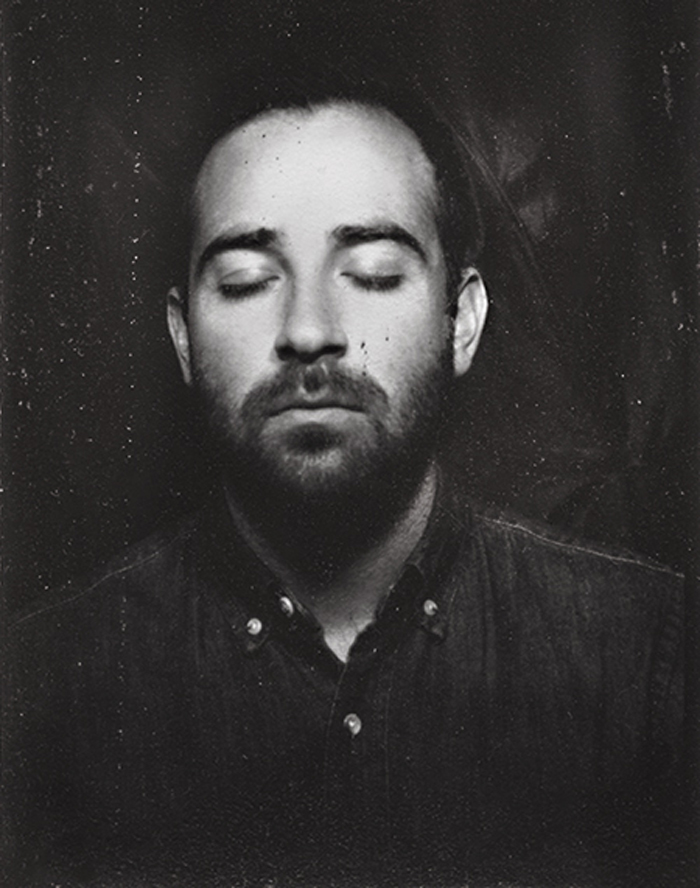

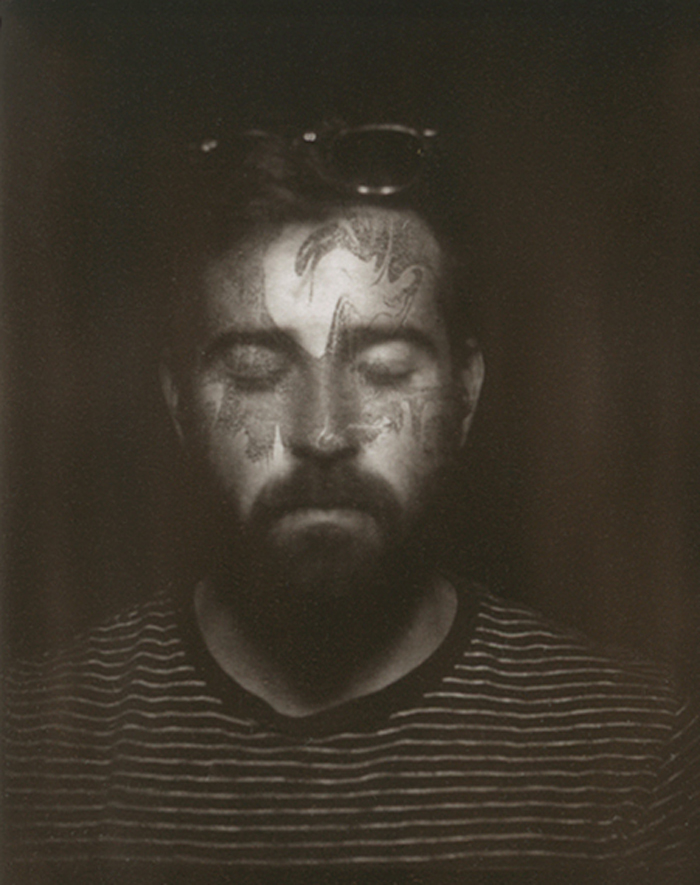

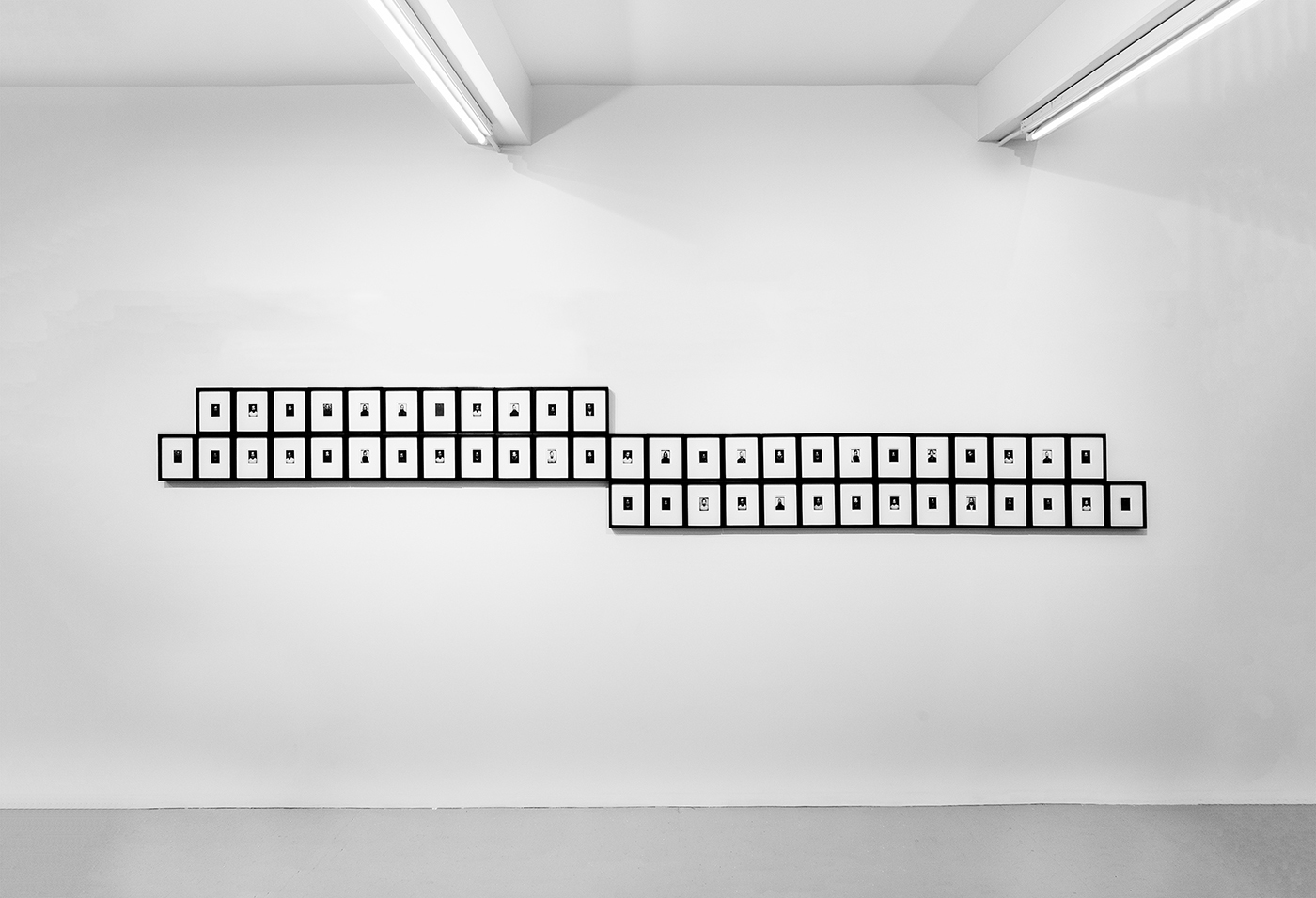

I was in Berlin at an artist residency and that evening was so strange and surreal—I was completely aghast and did not know what to think. I popped into a photo booth cabin simply seeking refuge, I wanted to be in a small, quiet space and that was my best bet in a public space. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine a future that might look different from what I knew was to come, and I made a picture (or four) of that moment by inserting a coin into the machine. In that moment I felt a symbiotic relationship with the booth, it became my collaborator. It was powerful to release control of the picture-making process, centering my experience and letting the machine make a picture of this being mourning in its womb. Almost a year later the idea for this project surged and when deciding what shape the project might take, I thought of that moment in that photo booth in Berlin. I realized it was a perfect way to make the work on-the-go and the process itself set the parameters for the formal elements of the work: four unique images, each a standard size, all black-and-white analog images, varying chemistry markings. From then on I began to draw parallels and connections. One day sitting inside the booth I noticed how much it mimicked the Catholic confessionals of my youth, which I hated, and how this was a great opportunity to reclaim that experience. Each time I got to make a confession in my very own terms. The ritual was for me. I was fully aware that these images would eventually be shared publicly so I focused on my own experience, the rest would come later. Once the objects went on the wall they became something else for me, they became public property in a way, they became a shared experience. People often ask me if I remember what I was thinking in each photo—which future was I thinking of? The answer is no, I don't remember, and I don't really care to. I'm more interested now in the conversations we can have about what feelings the work incites in the viewer, about global migration.

CONTOS —

Imagined Futures is presented as “50 seemingly identical self-portraits.” This alludes to the idea that the intentionally similar imagery you present is concealing an unseen element that is not fully represented in the frame. The viewer is presented with images that look almost identical, and yet the work suggests that a distinguishing variable is unseen.

How do you balance the content that is seen and the content that is suggested in its absence? How do you balance the concrete with the ambiguous? What motivates you to leave the viewer in the space between knowing and the unknown?

SOLDI —

I speak earlier about layers, and this has a lot to do with it. I think of this very intentionally in my work. I try to make work that is specific enough that it guides the viewer in a certain direction, and then I purposely allow for a certain amount of abstraction and universality so there is room for curiosity and imagination. An earlier project titled "Life Stand Still Here" presented works that were fairly abstracted in nature, and in that case, I used very specific titles to nudge the viewer toward a general direction. I'm not a fan of the age-old excuse "the work is about whatever you want it to be." I am very intentional with my motives but I think there's nothing worse than spoon-feeding the viewer. So that "unseen" content is where the magic happens. Once the work is on the wall, I'm not seeking a specific reading of the work, I'm rather hoping for a general emotional response. The work becomes a mirror, and each viewer will project their own experiences onto it—whether I want it or not.

The work becomes a mirror, and each viewer will project their own experiences onto it—whether I want it or not.

CONTOS —

This interview series is part of our larger analysis of how artists in the 21st century are advancing lens-based media, and how lens-based media has become ubiquitous.

Can you speak to your trajectory with the medium? How have you seen the medium evolve in the past 20 years, or throughout your career? What speculations, hopes, or concerns do you have for the use of lens-based media in the future?

SOLDI —

I reside firmly in the photography community, that's where I've "grown up," but I have not taken a picture in a very long time.* The last project I made for which I went out and made photographs with a camera was almost 10 years ago. Over the last decade, I've moved from taking pictures to manipulating pictures, to getting something else to take the picture for me, to working with archives and found footage, and lately, I've been working with printmaking, laser etching on velvet, moving image, installation, and sculpture. The photography world is very siloed. While most fine arts majors tend to interact and study different mediums, photography programs continue to be segregated from the rest of the art world. We have our own magazines, our own festivals, our own review events, our own art fairs, our own art centers, etc. I think we do ourselves a disservice by not having a closer relationship with other mediums. Many of the most exciting artists working today in photography are re-inventing the medium through collage, installation, sculpture, performance. I hope in the future we can decentralize photography and continue to invite more possibilities for experimentation.

*When I say that, I refer strictly to my fine art practice: I take pictures daily with my phone, and I have an active commercial photography business.

Biography

Rafael Soldi is a Peruvian-born, Seattle-based artist and curator. He holds a BFA in Photography & Curatorial Studies from the Maryland Institute College of Art. He has exhibited internationally at the Frye Art Museum, American University Museum, Griffin Museum of Photography, Greg Kucera Gallery, G. Gibson Gallery, Connersmith, PCNW, and Vertice Galeria, among others. Rafael is a 2012 Magenta Foundation Award Winner, and recipient of the 2014 Puffin Foundation grant, 2016 smART Ventures grant, and 2016 Jini Dellaccio GAP grant; he has been awarded residencies at the Vermont Studio Center and PICTURE BERLIN.

His work is in the permanent collections of the Tacoma Art Museum, Frye Art Museum, and the King County Public Art Collection. He has been published in PDN, Dwell, Hello Mr, and Metropolis, among others. Rafael is the co-founder of the Strange Fire Collective, a project dedicated to highlighting work made by women, people of color, and queer and trans artists.